A Brief Ceasefire in the War on Drugs

NORML ad from March 1979 Playboy

After Nixon waged an indiscriminate all out war on drugs, his immediate predecessors saw the issue as a bit more nuanced. In April of 1974 President Gerald Ford assembled a task force of senior officials from a dozen governmental agencies to look into the current drug policy’s efficacy and make recommendations for appropriate changes going forward. The resulting report, known as the White Paper on Drugs Abuse, found ‘a significant need to better coordinate and manage the federal drug program’ and advised authorities to more-or-less turn a blind eye to ‘street level’ crimes, arguing that resources would be better spent ‘on the development of major conspiracy cases against the leaders of high-level trafficking networks’. The authors of the White Paper also suggested that ‘not all drug use is equally destructive,’ and cited heroin, amphetamines, and barbiturates as the most dangerous. (Note the irony that two of the three most dangerous drugs can be legally obtained from most physicians—amphetamines are Schedule II and barbiturates are Schedule IV!) These two distinctions seem incredibly obvious today, but they were quite progressive at the time.

Ford wasn’t the first U.S. President to ask for a report on the effects of marijuana, nor was he the first to ask for a report on the efficacy of drug policy, but he did seem to be the first President open to considering change based on the report’s findings. Sent in a press release dated October 14, 1975 the President directed Federal agency with direct responsibility to respond within 60 days ‘to assure prompt implementation of [the] report.’ In the same press release he also directed the report be released to the public in order to ‘refocus the current public dialogue on drug abuse’. There was a focus on realistic expectations and identifying and prioritizing specific goals. When running against Jimmy Carter in 1976, Ford adopted a much harsher stance against cannabis use, but the actions of his administration were far tamer than those of Nixon’s—or, later, Reagan’s or Bush’s. While he didn’t make any pro-cannabis changes to the existing legislature, he pushed for a reinterpretation of its terms. One that portrayed non-violent cannabis users as regular people who presented no harm to society. (Like his son, who controversially admitted to having smoked cannabis. Ford responded by condemning his son’s cannabis use while at the same time praising his honesty.)

While President Ford adopted a more conservative approach towards cannabis in his 1976 election campaign, Jimmy Carter was openly in favor of decriminalizing cannabis on a federal level. Just six months after entering office Carter boldly proposed legislation that would replace imprisonment with civil fines that don’t carry criminal charges for offenders carrying less than an ounce of cannabis. In a March 15th, 1977 NY Times article Senior Advisor Dr. Peter Bourne, head of the new Office of Drug Abuse Policy, was quoted as saying, ‘[the administration] will continue to discourage marijuana use, but we feel criminal penalties that brand otherwise law-abiding people for life are neither an effective nor an appropriate deterrent.’ Carter asserted that ‘drug policies here are more punitive than in other democracies, and have brought about an explosion in prison populations’—this turned out to be a prophetic view as well, with the number of incarcerated non-violent drug offenders jumping from 50,00 to 400,000 between 1980 and ‘97. Carter maintained a hardline against heroin, but was notably at odds with the government’s official stance on cocaine and cannabis.

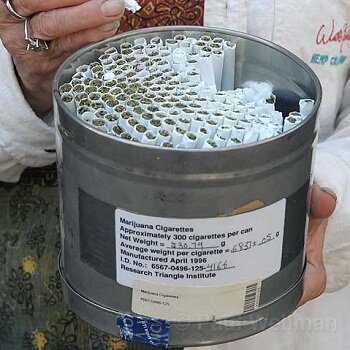

In 1977 the Senate Judiciary Committee voted to decriminalize less than an ounce of marijuana. In 1978 the Compassionate Investigational New Drug program, which provided medical marijuana for a very select few, was established. (This came on the heels of a landmark Supreme Court ruling in favor of glaucoma patient Robert C. Randall.) While he pushed through cannabis law reforms, Carter drew much criticism for his laissez-faire attitude towards responsible cannabis consumption from conservative pundits and politicians—like the actor/radio personality Ronald Reagan, for instance. And then, in July 1978 the Washington Post published the article ‘Carter Aide Signed Fake Quaalude Prescription’ and the Carter administration lost pretty much all credibility when it came to drug law. Bourne was caught writing a prescription for a staff member under a false name—and NORML leader Keith Stroup outted his cannabis and cocaine use…—so from then on, even after Bourne’s resignation, the subject was seldom brought up in a very out of sight out of mind kind of way. After a decade of relative reprieve from the war on drugs the ceasefire ended.