Reagan's War on Drugs

After enjoying a brief reprieve in the 1970s, President Ronald Reagan went after cannabis with a renewed vigor. In a radio address on October 2, 1982 President Reagan called for ‘full scale anti-drug mobilization’ and declared ‘Drugs are bad, and we’re going after them…We’ve taken down the surrender flag and run up the battle flag. And we’re going to win the war on drugs.’ Under his administration, new draconian laws were put into place that cut into citizens rights and directly contradicted Reagan’s stance on limiting government. Like the Shafer Report that was compiled during the Nixon years—and the Laguardia Report before that—the National Academy of Sciences published another study that was at odds with the negative publicity cannabis had been receiving since the 1920s that, like Nixon, Reagan altogether ignored. Joseph McNamara, a former police chief in both Kansas City, Missouri and San Jose, California, put it this way; ‘The drug war is a holy war […] and in a holy war you don’t have to win, you just keep fighting’. Reagan convinced Congress to change the long standing Posse Comitatus Act (in place since 1878) to allow military forces to be used as law enforcement on U.S. soil, and then cut social programs to supply police with military equipment and training. And with that the War on Drugs went from figurative to literal.

In 1982 the Supreme Court ruled in U.S. v. Ross that police had the right to search containers found in a person’s vehicle based on probable cause because ‘Contraband goods rarely are strewn across the trunk or floor of a car; since by their very nature such goods must be withheld from public view, they rarely can be placed in an automobile unless they are enclosed within some form of container.’ The problem with this is that this decision is predicated on the fact that police are given the authority to determine whether or not probable cause exists and, as Justice Marshall pointed out in a dissenting opinion, ‘[a warrant] issuing magistrate must meet two tests. He must be neutral and detached, and he must be capable of determining whether probable cause exists for the requested arrest or search. This Court long has insisted that inferences of probable cause be drawn by "a neutral and detached magistrate instead of being judged by the officer engaged in the often competitive enterprise of ferreting out crime."‘ This ruling expanded on ‘the automobile exception’ that had already been attached to the fourth amendment right against search and seizure. Nevertheless, the ruling represented a diminishment of citizen rights and marked the beginning of arguably the most aggressive government campaign against drug use—a campaign that was carried out at the expense of American citizens’s civil liberties.

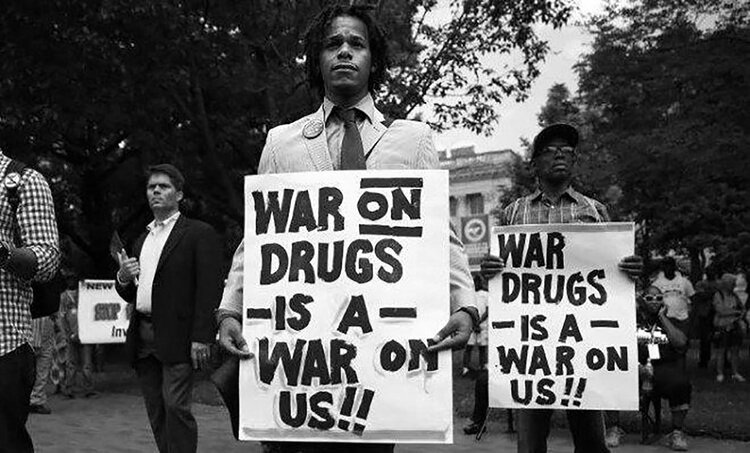

In 1984 the Supreme Court continued to chip away at the fourth amendment when they ruled in Oliver v. U.S. that ‘open fields do not provide the setting for those intimate activities that the [4th] Amendment is intended to shelter from government interference or surveillance’, meaning that law enforcement didn’t need a warrant to search private property—law professor Steven Wisotsky referred to the precedent set as ‘the drug exception to the Bill of Rights’. That same year congress passed the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which increased drug penalties and mandatory minimums. The new law also made it easier for law enforcement to seize assets from suspected cannabis producers and distributors—to the point where almost half of the police department budgets in the United States depended on drug seizures and forfeitures! The legislature allowed for seizures even before charges were brought, and many of those who were ultimately found innocent didn’t bother trying to take back their assets because of the hurdles they’d need to jump to do so. Between 1981 and 1987 government seizures grew from $100 million to over $1 billion and about 80% of seized property was from individuals that were ultimately never charged. The sale of drug paraphernalia was made illegal and the incarceration rate for non-violent drugs offenders rapidly increased—and by far the majority of those charged were from minority communities. The targeting of African American communities was so obvious that Reagan’s drug laws were referred to as the new Jim Crow because, as the ACLU director Ira Glasser put it, ‘drug prohibition has become a successor system to Jim Crow laws in targeting black citizens, removing them from civil society, and then barring them from the right to vote’. Between 1980 and 1989 the prison population doubled and there were more black prisoners than white for the first time since slavery. The stricter enforcement of drugs laws led to a 36% increase in law enforcement jobs and an 86% increase in prison jobs, paid for with money taken from social programs and suspected drug dealers (again, 80% of whom were never charged).

While Reagan turned his focus to international affairs, First Lady Nancy Reagan joined the fight and launched her Just Say No campaign. Like with Elvis, who was both staunchly anti-drug and addicted to prescription medications, Nancy was a somewhat unlikely drug crusader considering her not-to-private chronic use of prescription tranquilizers. Just Say No was the basis for a number of drug abstinence programs developed in the 1980s and 90s, the most famous of which probably being the Drug Abuse Resistance Education program (D.A.R.E) founded in 1983. Parent groups like the National Federation of Parents for a Drug-Free Youth and drug ‘boot camps’ like Straight, Inc. popped up all across the United States. Following the Court’s trend of limiting the scope of the fourth amendment, in 1985 the Court deemed school officials had the right to frisk and strip search students, as well as go through their bags and lockers. These programs proved to be a failed experiment in drug prevention. Ross Anderson, mayor of Salt Lake City. called D.A.R.E. a ‘complete fraud’ that did ‘a lot of harm’. Straight, Inc. operations across the country were forced to shut down after reporters exposed abuse and confinement. Arnold Trebach, who founded the Drug Policy Foundation in 1986, cautioned that ‘because we so irrationally fear drugs as a nation, we say that you can practically destroy children to prevent them from using drugs.’ Turns out, the drug war was less a war on drugs than a war on the country’s most vulnerable citizens.